AUS Climate Changes

AUSTRALIA: A CASE STUDY FOR GLOBAL CITIES

During the summer of 2019-20 Australia was burning with devestation to the natural environment; wildlife species & habitat; air & water quality; increases in UHI effects; communities and the economy.

Australia is a “land of climate extremes”. This is especially true for our cities, which have become hubs of extreme summer temperatures. This past summer was the second-hottest on record for Australia, following the 2018-19 record, with average maximum temperatures more than 2°C above the long-term average.

Frequent and long heatwaves are having serious impacts on energy consumption, public health, labour productivity and the economy.

Even without global warming, cities already face a problem — the urban heat island effect, whereby inner urban areas are hotter than the surrounding rural areas. Urban heat islands are caused by factors such as pollution, energy consumption, industrial activities, large dark concrete buildings, asphalt roads and closely spaced structures.

Evidence from Australia’s major cities shows average temperatures are 2-10°C higher in highly urbanised areas than in their rural surroundings.

Water temperatures of estuaries, lakes and rivers have risen by 2 degrees since 2010 which is impacting on marine environments.

Governments and policymakers can use a variety of cooling strategies combined with community engagement, education and adaptation measures to cool Australian cities.

1. Green infrastructure

Green infrastructure includes parks, street trees, community gardens, green roofs and vertical gardens. In tropical and subtropical climate zones, like much of Australia, green infrastructure is a cost-effective cooling strategy.

Image: Green Roofs utilise roofspace that is unavailable at street level.

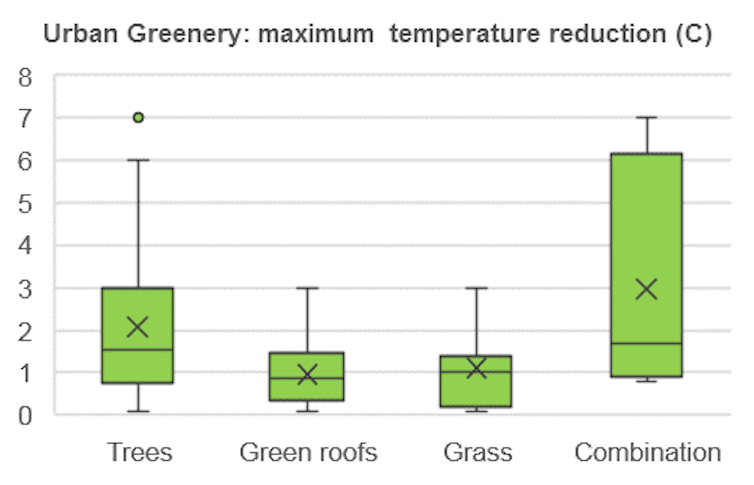

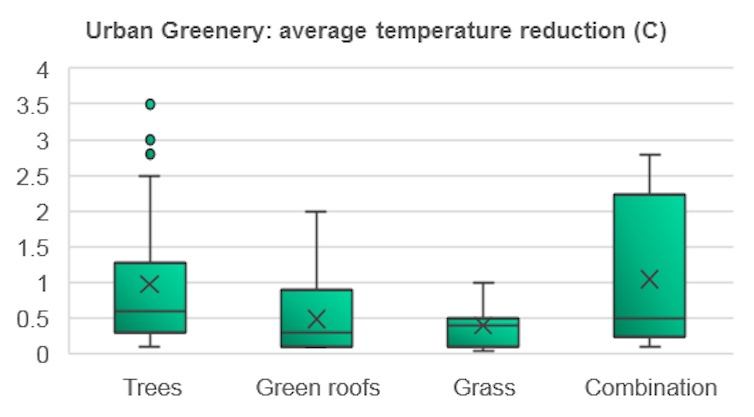

Evidence suggests a 10% increase in tree canopy cover can lower afternoon ambient temperatures by as much as 1-1.5C, as the chart below shows. Similarly, in parks with adequate irrigation ambient temperatures can be 1-1.5°C lower than nearby unvegetated or built-up areas.

Maximum (above) and average (below) temperature reduction potential of different urban greenery techniques

We can increase street tree canopy cover by planting more shade trees on footpaths, lanes and street medians. Where there is little space for parks and street trees, green roofs and walls may be viable options.

2. Water-sensitive urban design

The use of water as a way to cool cities has been known for thousands of years. Water-based landscapes such as rivers, lakes, wetlands and bioswales can reduce urban ambient temperatures by 1-2°C. This is a result of water heat retention and evaporative cooling.

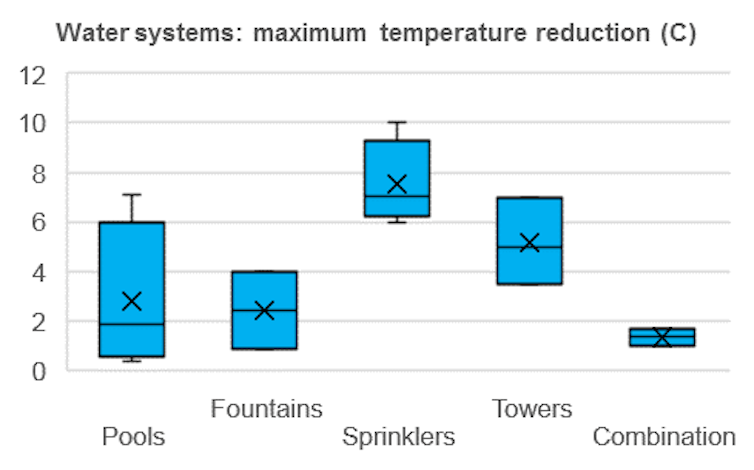

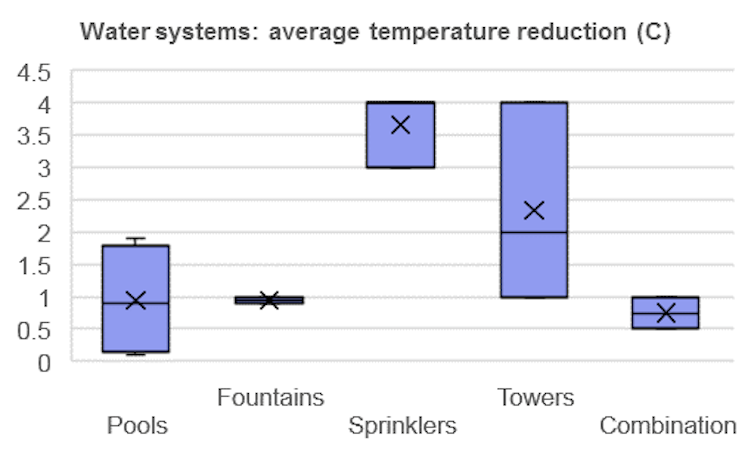

In addition to natural water bodies, various other water-based technologies are now available for both decorative and climatic reasons. Examples include passive water systems, like ponds, pools and fountains, and active or hybrid systems, such as evaporative wind towers and sprinklers. Active and passive systems can decrease ambient temperatures by 3-8°C, as the charts below show.

Maximum (above) and average (below) temperature reduction potential of different active and passive water systems.

Water-based systems are usually combined with green infrastructure to enhance urban cooling, improve air quality, aid in flood management and provide attractive public spaces.

3. Cool materials

Building materials are major contributors to the urban heat island effect. The use of cool materials on roofs, streets and pavements is an important cooling strategy. A cool surface material has low heat conductivity, low heat capacity, high solar reflectance and high permeability.

Evidence suggests that using cool materials for roofs and facades can reduce indoor temperature by 2-5°C, improve indoor comfort and cut energy use.

Maximum (above) and average (below) temperature reduction potential of different cool surfaces.

Cool materials commonly applied to buildings include white paints, elastomeric, acrylic or polyurethane coating, ethylene propylenediene tetrolymer membrane, chlorinated polyethylene, polyvinyl chloride, thermoplastic polyolefin, and chlorosulfonated polyethylene.

Lighter aggregates and binders in asphalt and concrete, permeable pavers made from foam concrete, permeable asphalt and resin concrete are standard cool pavement materials.

4. Shading

Shading can decrease radiant temperature and greatly improve outdoor thermal comfort. Providing shading on streets, building entries and public venues using greenery, artificial structures or a combination of both can block solar radiation and increase outdoor thermal comfort. Examples of artificial structures include temporary shades, sunshades and shades using solar panels.

5. Combined cooling strategies

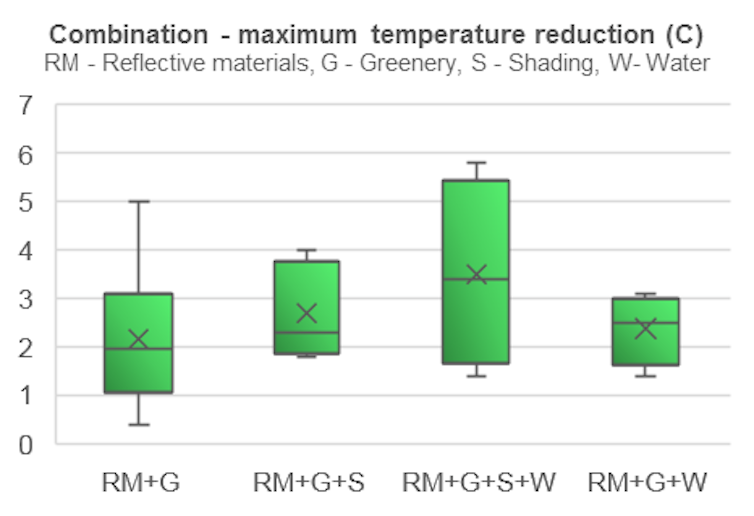

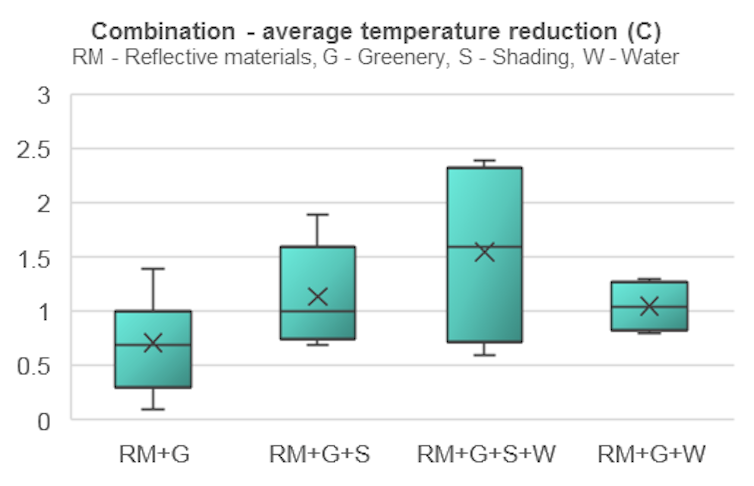

Performance analysis of various projects in Australia suggests the cooling potential of the combined use of the different strategies discussed above is much higher than the sum of the contributions of each individual technology, as the charts below show. The average maximum temperature reduction with just one technology is close to 1.5°C. When two or more technologies are used together the reduction exceeds 2.5°C.

Maximum (above) and average (below) temperature reduction potential for a combination of technologies.

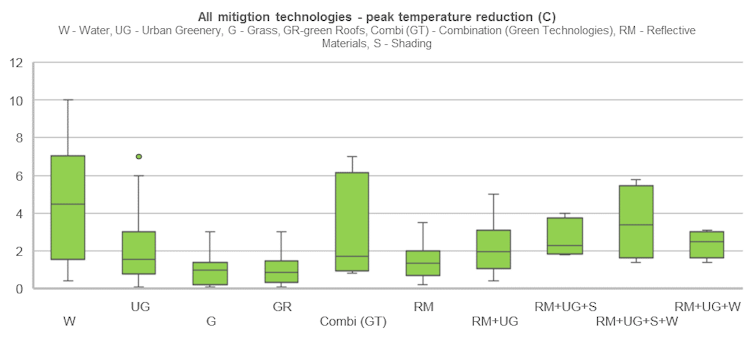

The chart below shows the peak temperature reduction for all cooling strategies.

Komali Yenneti et al, Author provided

6. Behaviour changes

People are significant contributors to urban heat through their use of air conditioning. The waste heat from air conditioners heats up surrounding outdoor spaces.

Projections show cooling demand in Australian cities may increase by up to 275% by 2050. Such a trend will have a great impact on urban climate, as well as increasing electricity use. If this is powered by fossil fuels, it will add billions of tons of carbon pollution.

Climate-responsive building design and adaptive design techniques in existing buildings can minimise occupants’ demand for cooling energy by reducing indoor and outdoor temperatures.

Cities must take a holistic, long-term approach

Local governments can prepare for and respond to heat events through emergency response plans. However, emergency responses alone cannot address other challenges of urban heat, including human vulnerability, energy disruptions and the economic costs of lower workplace productivity and infrastructure failures.

Long-term cooling strategies are needed to keep city residents, buildings and communities cool and save energy, health and economic costs.

SOURCE: THE CONVERSATION